Behind the Camera: Martha Swope

The story of NYCB's House Photographer 1957-1983

, January 26, 2021

A ballet may contain a story, but the visual spectacle... is the essential element. The choreographer and the dancer must remember that they reach the audience through the eye.

George Balanchine

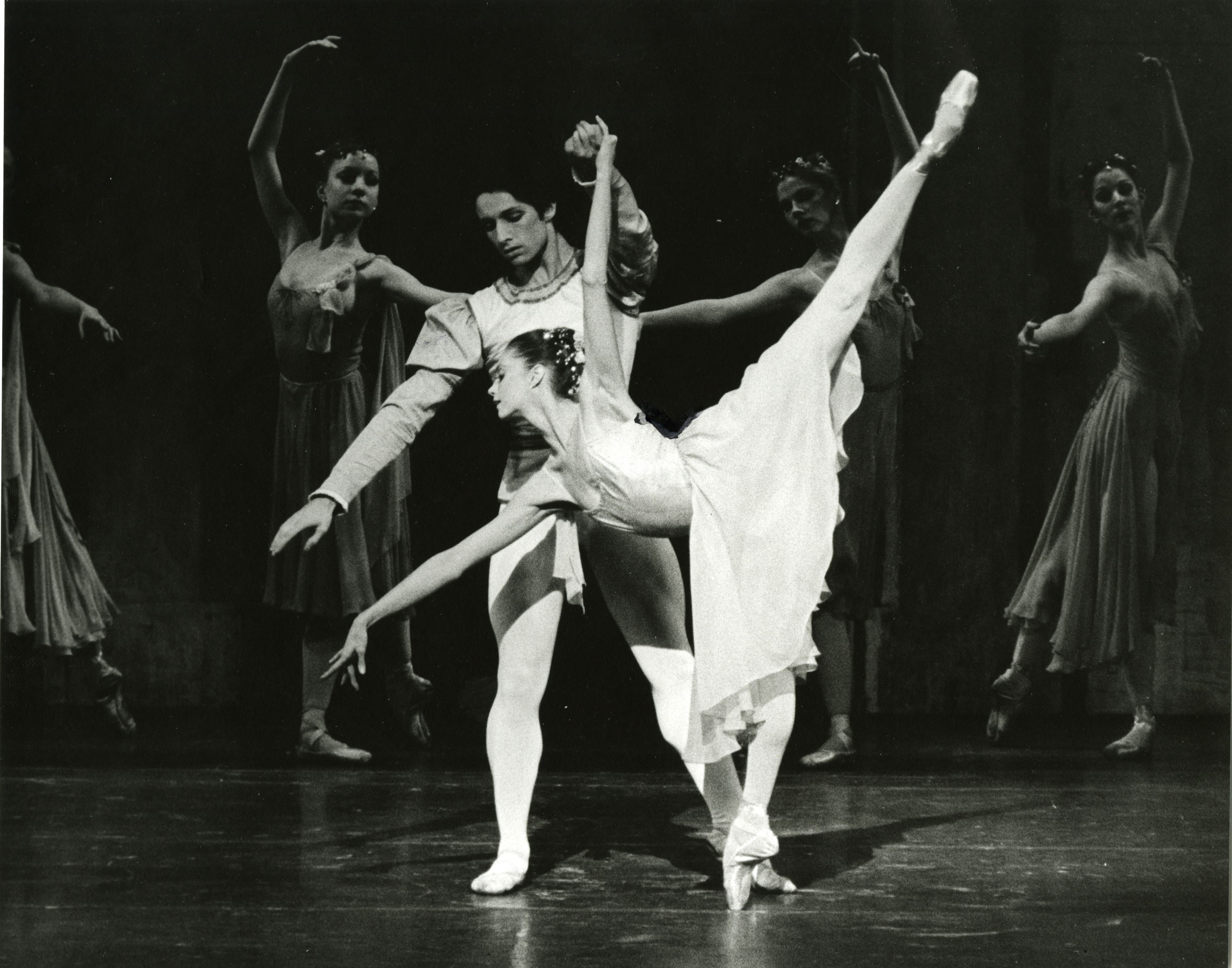

In the current moment of increased dependence on digital exhibition, while theaters remain closed and with live performances extremely rare, the visual archive takes on a new level of importance in experiencing and appreciating ballet. Beyond the filmed works we’re sharing via the Digital Seasons and excerpted performances, New York City Ballet is blessed to have an extensive photographic record of dancers captured mid-movement on stage and in rehearsal, instances of ephemeral artistry made permanent; but what of the artistry involved in creating that record?

Martha Swope, NYCB’s house photographer from 1957 until Balanchine’s death in 1983, told an interviewer, “I’m not interested in what’s going on on my side of the camera. I’m interested in what’s happening on the other side.” While there have been many who have photographed the Company over the years—Walter Owen, Fred Fehl, Paul Kolnik, Steven Caras, and more—Martha Swope’s trajectory, from dancer-hopeful to School of American Ballet student to Company photographer for a notable number of years, and legacy as a mentor to those photographers who followed, demonstrate that her background, personality, and talent warrant inclusion her in the Company’s own history.

Swope’s origin story is the stuff of Broadway/Ballet legend. Born and raised in Texas, she had an early interest in photography, but her goals as an artist were focused primarily on dance; after a year at Baylor University in her home state, Swope was accepted to the School of American Ballet and moved to NYC to attend. One of her fellow students was none other than Jerome Robbins, who had been performing and creating works for NYCB since becoming the Company’s Associate Artistic Director in 1949, before focusing more extensively on choreography for Broadway. In 1957, Robbins had begun work on West Side Story to keep his dancing chops up to snuff, Robbins was taking class at SAB, where he met Swope and connected with her over a shared amateur photography hobby, with Robbins eventually offering Swope use of his personal darkroom. Then, he asked her to capture a day’s work in the creative process behind West Side Story. The photos she took have become essential records of a watershed moment in Broadway history; one was selected for print in Life Magazine, thereby launching, in essence, her career as a professional photographer.

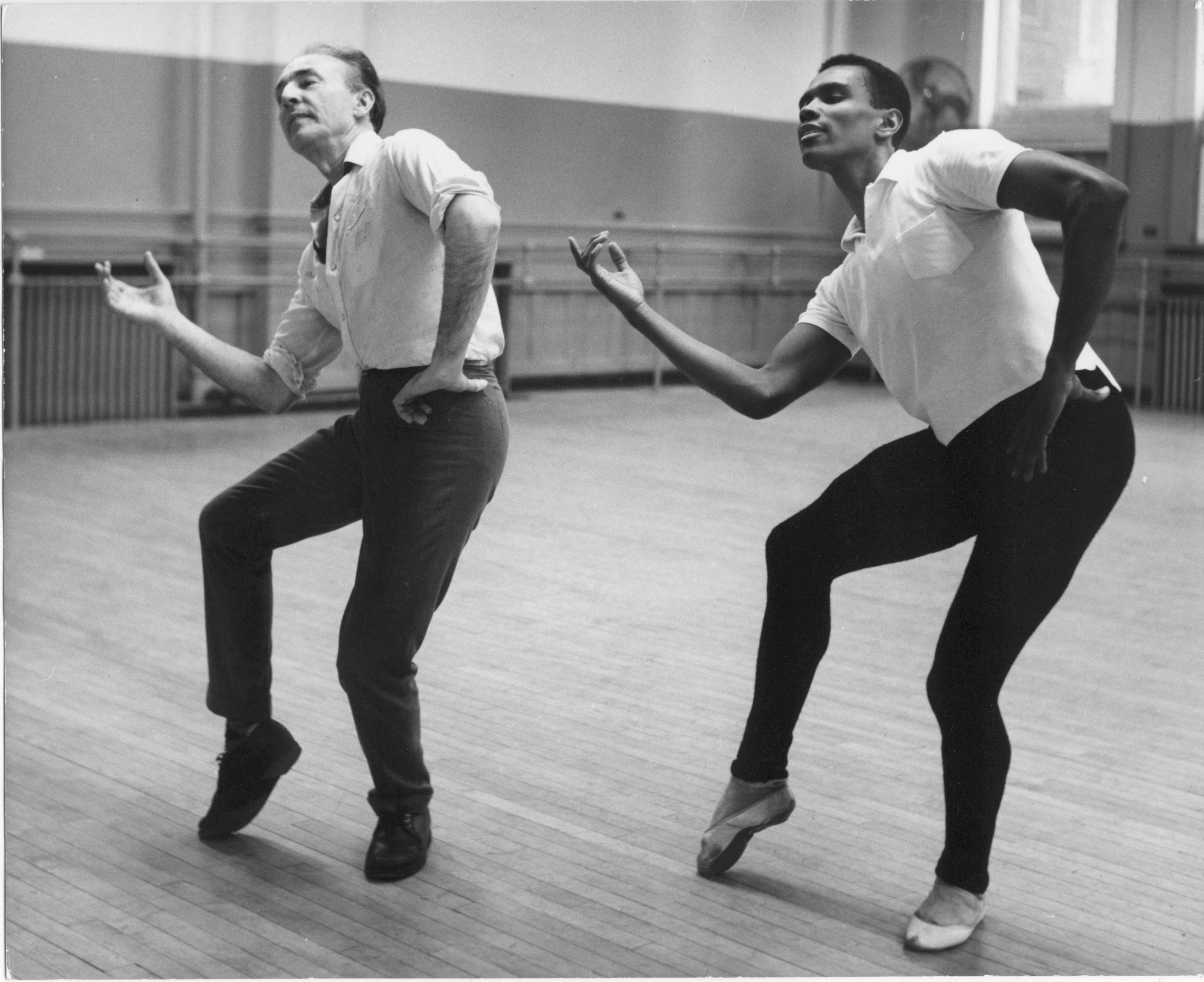

Returning to class at SAB, Swope was again pulled from the barre, this time by NYCB founder Lincoln Kirstein, who asked her to record a similarly history-making moment—in the ballet studio: the creation of George Balanchine’s Agon. During this first official “assignment” for the Company, none other than the ballet’s score’s composer, Igor Stravinsky, was in attendance, and Swope’s photographs include the two titans working

As Swope told The New York Times in a 2012 interview, rehearsals were “where you see the creativity and the interchange, how it grows to what it comes to be onstage.” As was true from her first photographic efforts, Swope would attend and shoot works-in-process throughout her career, watching rehearsals not only to become familiar with new choreography but to capture those exchanges between artists which are even less permanent

In a short piece in New York Magazine from September 1975, Swope outlined the importance of superior organizational habits to maintaining her incredibly prolific career; at the time, she was already the house photographer for NYCB and the Martha Graham Dance Company, as well as the sought-after photographer for much of Broadway, including producer David Merrick and producer/director Hal Prince, who insisted that she shoot all of their plays. “So many of my jobs have to do with my being dependable,” said Swope, taking a typical selfless stance. “Deadlines in this business are very tight. I take the photographs that go into the publicity that puts the show on.” As the piece recounted, Swope once shot five performances in four cities—Detroit, Boston, Washington, and New York—in just 73 hours. “There is just no way I am going to go to bed or get up in the morning without looking at my calendar. It runs my life.” She used the apartment below her own as a studio, set up to capture perfectly posed (and poised) records of artists from the ballet and Broadway stage; as Carol Rosegg, an early assistant and dedicated student of Swope’s, recalled, the apartment’s bathroom served as the darkroom.

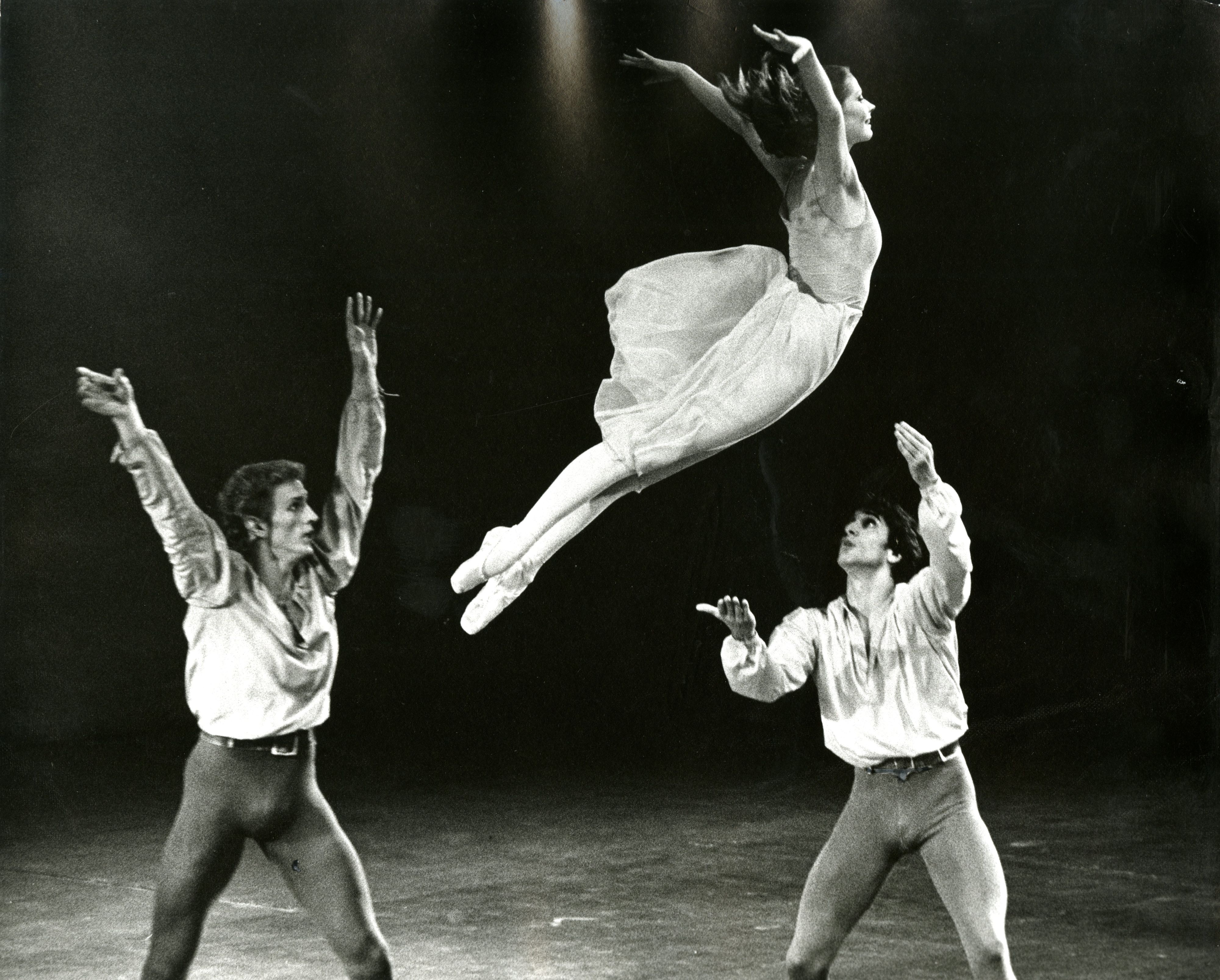

Swope’s career aligned with technical developments in camera and lighting equipment that made capturing live performances more feasible. Rosegg described to the Times the photographer’s practice of sketching stick-figures in possible setups throughout a performance; this was particularly helpful in that Swope often had very

Martha went on to shoot over 800 Broadway shows. And she did it under adverse conditions at something called “the photo call”—the two-to-four hours allowed by the unions after a dress rehearsal, when actors and crew were exhausted. … Martha got dozens of extraordinary pictures at photo calls. … Often the shots had to be done backwards—from the end of the show to the top. With a bunch of very tired actors. But there was Martha, saying, ‘Oh, please sing that lovely song about “Home” for me,’ and, suddenly, exhausted, self-conscious actors were performing at their best.

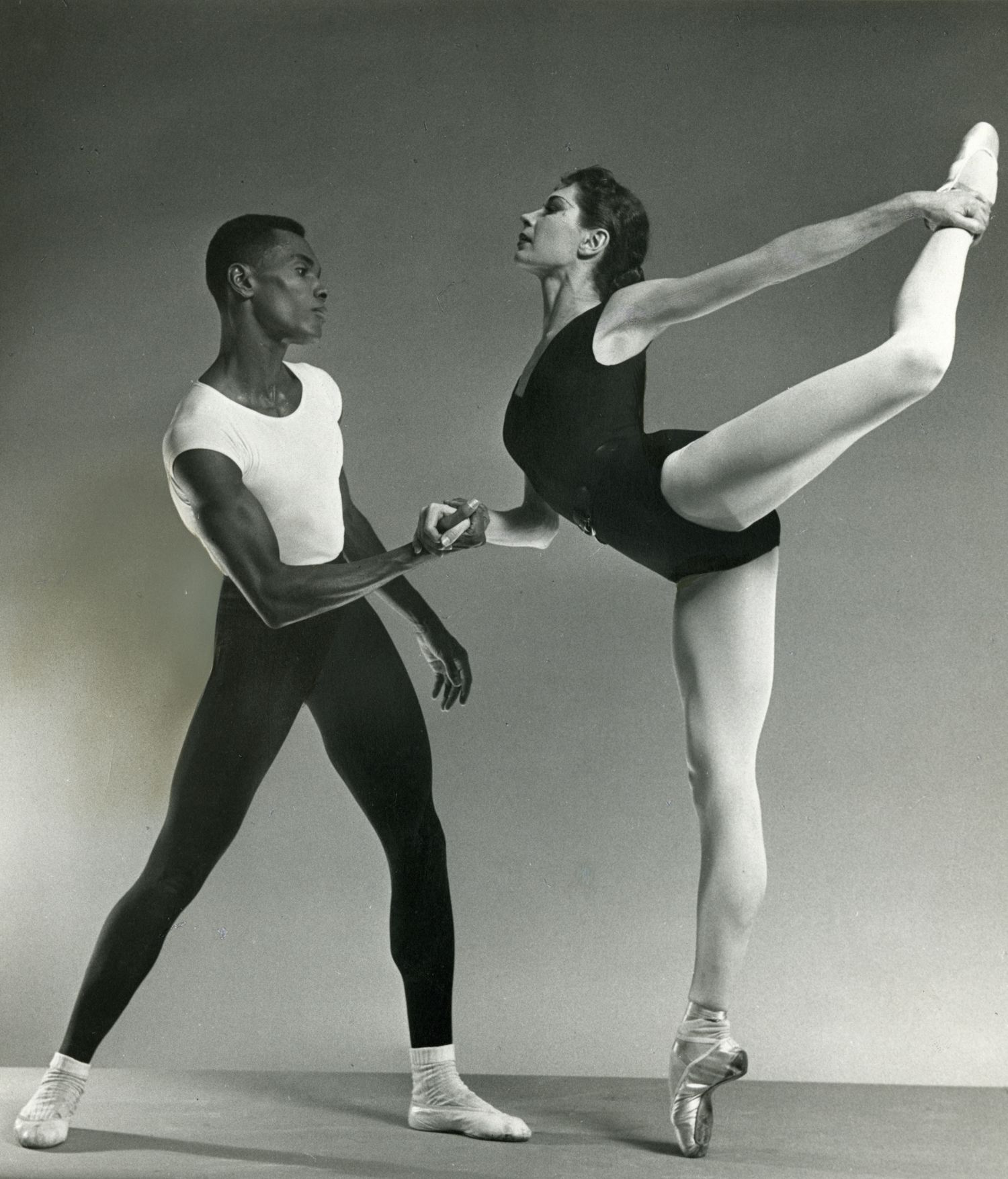

Though known and appreciated for her “gentle temperament and Southern manners” and resistant to public recognition, the moment Swope entered a theater or rehearsal space or photography studio, performers were known to let out a sigh of relief. “She taught me never to shoot anyone en pointe until they had fully extended over their arch,” noted Rosegg. “Fingers, hands, necks—all perfect.” Delia Peters, a friend of Swope’s and former dancer with NYCB, echoed this sentiment: “Having been a dancer, she understood the timing. She understood what they were going to do, she understood where the pictures were going to be.” And despite having two assistants to handle printing, taking job orders, and keeping her cameras loaded between shoots, Swope still made all selections from the negatives. “And she was a master retoucher,” said Rosegg. “In those days you would sit with a single-edge razor blade scratching out wrinkles one at a time.”

The care and thoughtful, instinctual eye Swope brought to each assignment resulted in iconic photos throughout her career. “She was the first photographer to take a shot from the back of the stage of the ballerina taking a bow,” noted Dr. Jeanne Fuchs, Swope’s close friend and confidant, and a fellow former SAB student. “In

Besides ballet and the theater, Swope was also an inveterate animal lover, known to rescue stray kittens and keep pet dogs in the studio. In 1964, her photographs of Balanchine and his beloved, acrobatic cat Mourka provided the impetus and material for Balanchine’s then-wife and former NYCB principal dancer Tanaquil Le Clercq’s book, Mourka: The Autobiography of a Cat. Per Dr. Fuchs, Swope’s interests also included travel and other pursuits: “Martha was a great reader; she also memorized poetry, which she loved, including the entire Prologue of the Canterbury Tales. … She was extremely sensitive and loved all games – word games, card games, and puzzles (jigsaw and crossword). … She went to Machu Picchu, Easter Island, the Galapagos, and many trips to London, Madrid, Paris and Rome, sometimes for work, but mainly for amusement.”

In a 1979 interview with Walter Terry for On Point: American Ballet Theatre, Swope described her role as follows: “I think that photography is a craft, a tool. The art is in front of the camera. The art is the dancer… the actor. As a craftsman, you take, from what they are giving, what pleases you and what touches you.” A record-keeper of fleeting moments of beauty, talent, and occasionally perfection, the photographer serves the culture at large; but Swope has definitely undersold the importance of her own unique approach and perspective. Siobhan Phillips, writing for Artforum on Swope’s death in 2016, counters: “Swope’s career included the ‘dance boom’ of the 1960s and ’70s, and she understood how to feed curiosity about an art form while never travestying the artistry or diminishing the admiration it deserves. Her rehearsal photographs show the sweat and scuffed shoes—also the camaraderie and effort. … Her pictures aren’t about exposure or exploitation or pride. What she photographed, she understood.”

In 1976, a young Balletomane named Paul Kolnik, who’d moved from Chicago to see New York City Ballet seized by the compulsion to ''bear witness, to testify to 'that great ball of fire Mr. B and Lincoln Kirstein made”—took on a year-long assistantship with Swope. Branching out on his own, he would eventually become the Company’s go-to photographer following Swope’s retirement, and like his own mentor, train the up-and-coming ballet-loving photographers that followed, including Erin Baiano, his current NYCB photography colleague.

In 2010, Swope donated her life’s work to the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. Per the Library’s description, “The collection consists of over 1,520,000 images, black and white and color, on contact sheets with corresponding negatives (mostly 35mm and 120), transparencies, slides, and prints taken from ca. 1955-2002 (bulk dates 1957-1994).” Much of this collection is viewable online, for ballet lovers, dancers looking for examples, and, perhaps, burgeoning dance photographers. As Swope told the Times in 2012, “Now I think it’s somebody else’s era.”

All photos by Martha Swope