The NYCI Fall Session 2022

Hear from the Choreographers of the Latest Institute Commissions

, January 24, 2023

Discovering new and unexpected voices in contemporary choreography remains one of the abiding pleasures of experiencing the New York Choreographic Institute’s seasonal outputs. Twice each year, a trio of dancemakers is given the time, space, and resources to create a new work with School of American Ballet or New York City Ballet dancers; the results are often challenging, surprising, and always exciting. The most recent presentations are no exception.

Choreographers Raja Feather Kelly, Caili Quan, and Stephen Shropshire each brought their unique histories and vocabularies to their casts of Company members, whose classical training combined with an openness to the unfamiliar are essential elements to the creation of these works. Just as important are the contributions of dramaturgs Sarah Lunnie and Risa Steinberg, and filmmaker Quinn Wharton; the use of NYCB studios; and the fruitful discussions between the choreographers and the Institute’s Artistic Director and NYCB Principal Dancer Adrian Danchig-Waring.

We spoke with Feather Kelly, Quan, and Shropshire about the process of developing these works, creating on Company dancers, and sharing their visions via the dance films streaming here.

"I always start with the music," says Caili Quan. Born to a Chamorro Filipino family in Guam, Quan moved to the United States to study dance in New York. She was a dancer with BalletX in Philadelphia from 2013 to the start of the pandemic in 2020; by August of that year, she was a full-time, New York-based choreographer. "Whenever I get a commission, I make a very large playlist and narrow it down from there. Sometimes it starts with an idea, but usually music is one of the first things that falls into place before everything starts organically coming together. Getting to show people the music is such an integral part of a dance."

For her work Dignity in Restraint, created on NYCB Dancers Sarah Harmon, Jules Mabie, Samuel Melnikov, Quinn Starner, and Claire Von Enck, that music was Beethoven's String Quartet No. 12 in E-flat major, a piece Quan describes falling in love with upon hearing it. "I just kept coming back to it, it was a really punchy seven-minute song," she says. "Beethoven has a way of weaving in many different emotions in such a short period of time, so it felt very human. If you look at the score, it's these crazy highs and lows that happen so fast, but it sounds so organic. So I was like, 'Man, that would be really fun to make a dance to.'"

The intensity conjured by the composition inspired Quan to dig into theories of emotion, landing on a structure of five core emotions that correspond to five major chords in the music: anger, disgust, fear, joy, and sadness. "We did phrase work by emotion, just to generate material," she explains. "And then when we started creating, I kept going back to some of those thematic steps, weaving it naturally through, hoping to match the extremeness of the music with a theme that sewed it all together. I usually don't use Beethoven—there are so many layers within the music that I hope I was able to bring to life via movement. I wanted to take on the challenge at the Institute, knowing that I would have the dancers that I had. It was a great opportunity to crack open some Beethoven as best I could for the first time."

The process was also more collaborative than usual for Quan, as this was the first work she's choreographed while eight months pregnant. "I just can't move the way I usually could," she shares. "I went with the natural instinct of where the dancers wanted to go next, so I asked that question quite a lot—'Where does your momentum want to go, what does it feel like musically?'

"The opportunity to work with a dramaturg, Sarah Lunnie, was also so incredible," she adds. "It was really nice to hear her feedback and chat with her about different ways the piece was moving forward. She helped add an extra layer of perspective to the work that I couldn't have found by myself.

"I've heard about the Institute since its inception," she continues. "I've kept a close eye on the choreographers that they brought in and the work that they were producing, and I was really happy to see films coming out when I couldn't make it to the showings. A lot of the time with making work, it's about the final product and that big performance, and I thought it was such a genius idea to create an incubator for the sake of choreographing. To make it more about the process. It's very appealing, getting time to research with resources for two weeks, with such young, hungry dancers. And the cast that I was given was so lovely. I had a really good time in the studio making the work."

Dignity in Restraint

After graduating from Connecticut College with English and Dance majors, Raja Feather Kelly performed with a number of contemporary choreographers, including David Dorfman, Zoe Scofield, Christopher Williams, Reggie Wilson, and Kyle Abraham; in each of their approaches to the art form, he discovered elements that inform his own choreographic approach. "I couldn't get all of that in one company. So I started my own," he says. "It's called the feath3r theory (TF3T), and we're a dance theatre and media company. We make a lot of work that's mostly about popular culture and ensemble building. That's what I think a lot about—building ensembles and worlds around them."

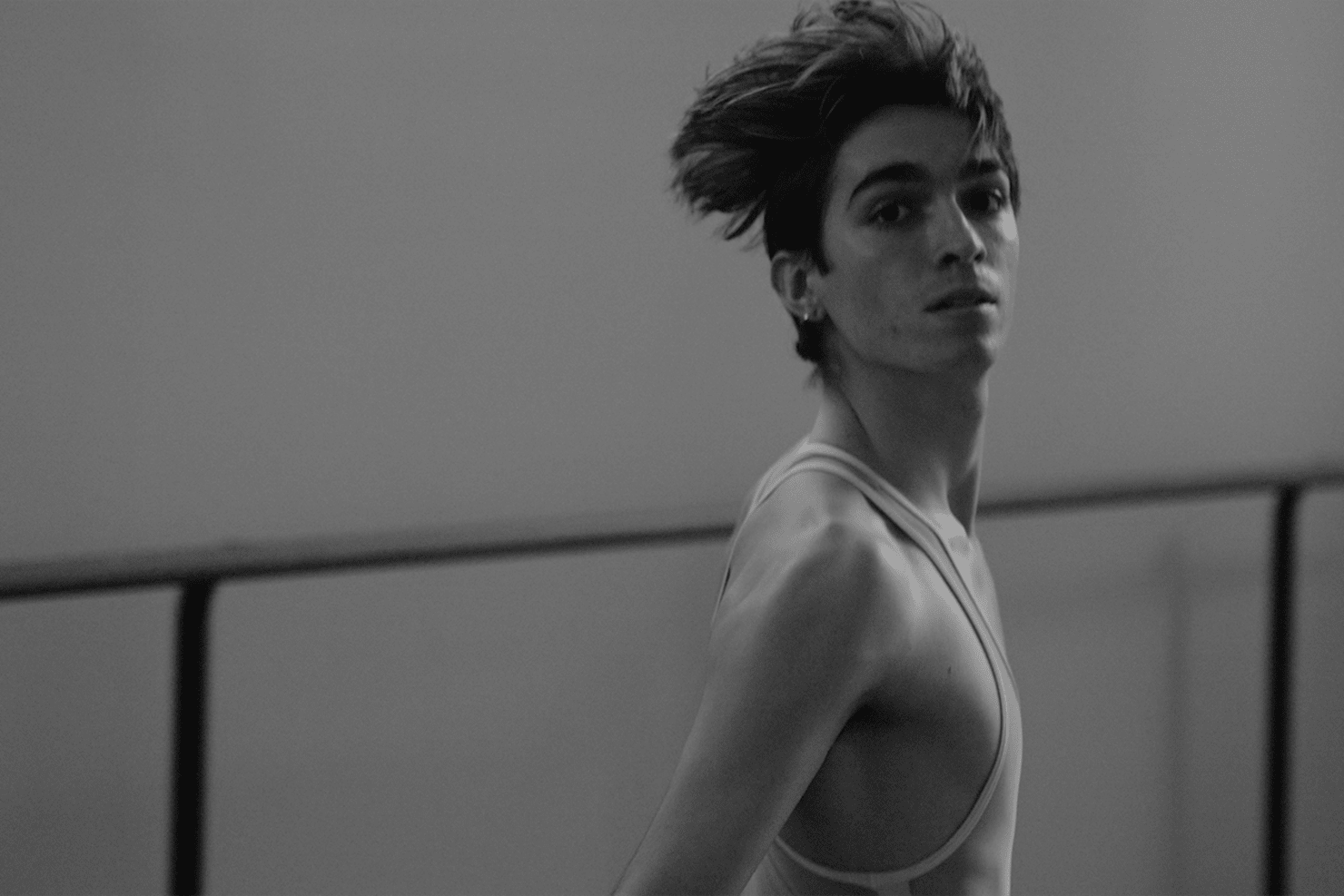

The "ensemble" he created his work Starlings on was composed of NYCB Dancers Dominika Afanasenkov, Olivia Bell, David Gabriel, Noah McAuslin, Ava Sautter, Grace Scheffel, and Anna Snellgrove. "They're so smart," he says, "and they're so direct, absorbent, and expressive, beautiful, and curious. They picked up material quickly and asked a lot of questions. I was able to bring a group of people inside my process—that doesn't always happen. But with this group, there was a nice interest shared between us to really dig deep and uncover. And it's also important to say that Risa Steinberg, who acted as dramaturg, had a sincere and genuine interest in the work and how I was making it."

Feather Kelly describes his process as beginning with getting to know the ensemble, then discovering how they might come together and why they might fall apart. "Once I got more specific, it was a phrase I had made, and an idea that I shared with the group that they hadn't heard of before—this idea of 'flocking,' which is a way of moving in which your shoulders always maintain a square relationship with the shoulders in front of you. So, if you're moving as a group, it constantly shifts who's leading and who's following, and it's almost imperceptible. On a human level, that's really exciting to watch—that navigation. On a more animal level, it's something that birds do quite easily. That's why I titled the work Starlings: It reminded me of these migrating birds. And, something about the way I imagined these birds was [similar to] the way that I was introduced to this ensemble—sprightly and curious and energetic and light and full of air. So in many ways, I made it for them, about them, with them.

"It's been a dream of mine to work with a ballet company," says Feather Kelly. "It's not something I think people might imagine I would be interested in. I am fiercely interested in what ballet can do and the language of ballet, and my more conceptual theatrical background being interwoven into that. Adrian and the performers were really welcoming to my ideas, and Risa was an incredible interrogator and really drew those ideas out." Though at first he'd assumed he'd select music by Tschaikovsky ("I should probably find something classical. It's ballet."), he was excited to learn from Danchig-Waring that the Institute supported the use of music by living composers, and among those available was American composer Missy Mazzoli, of whom the choreographer was already a fan. "I think the idea of being able to talk to a composer about what went into it really inspired me and was exciting for me—to think about a translation or development or an intersection of my work and [that of] another artist.

"It was a fast process," adds Feather Kelly. "But more than anything, it was a very deep process. And for that I'm forever grateful, and the ideas are still with me. So I have to do something about that at some point."

Starlings

"I wanted to participate in the Choreographic Institute because it offered such a unique and extraordinary opportunity: to develop work within the context of one of the most significant ballet organizations in the world, New York City Ballet," says choreographer Stephen Shropshire. As a graduate of The Juilliard School, which shares a campus with NYCB and its partner the School of American Ballet, and the founder of The Shopshire Foundation, dedicated to the "ongoing development and presentation of new choreographic work," he was more than well-suited for the opportunity.

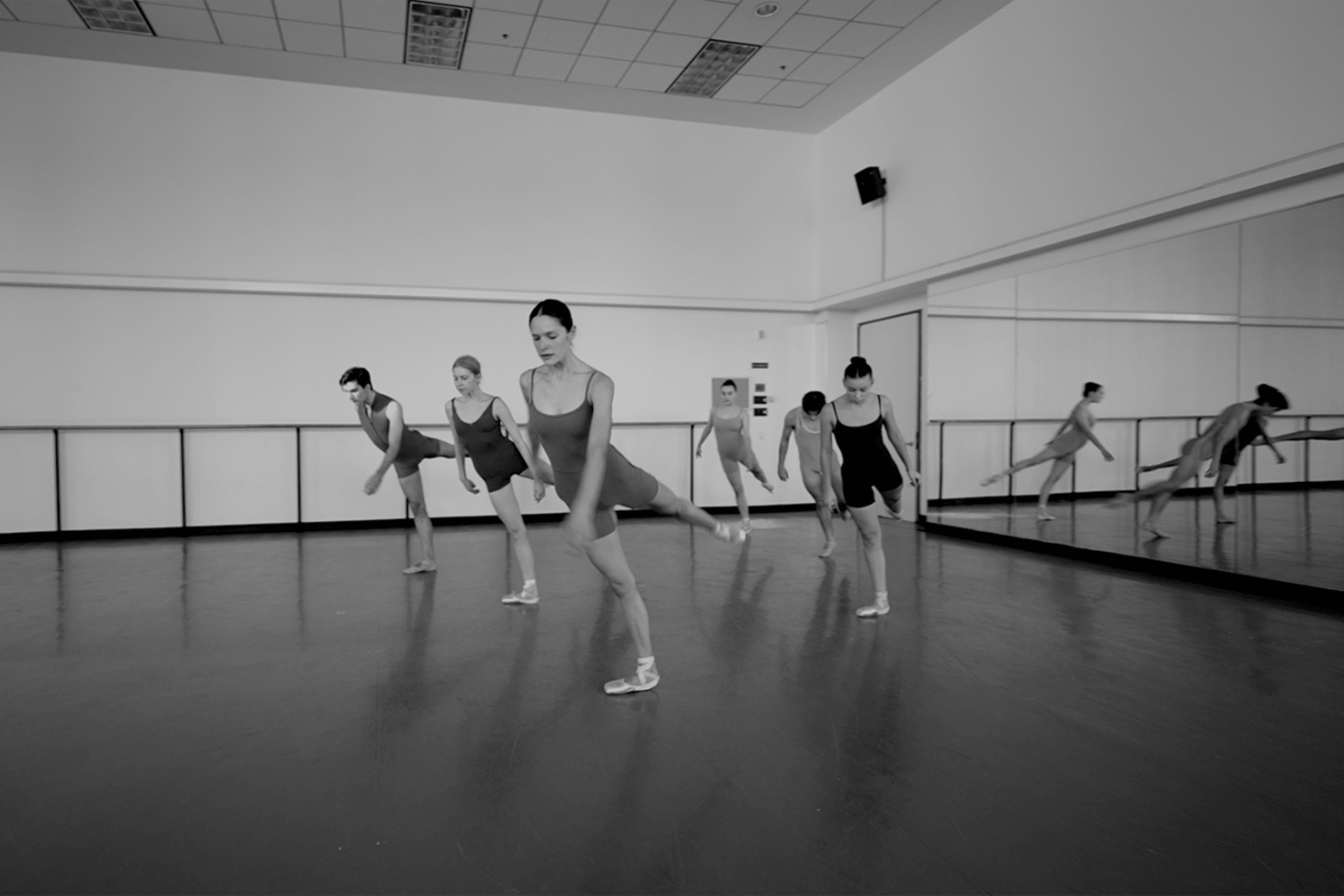

The Bagpiper's String Trio, the work Shropshire developed at the Institute, features a trio of NYCB dancers: Mira Nadon, Davide Riccardo, and Andres Zuniga. "It was a great pleasure for me to work with Mira, Andres, and Davide, who brought with them not only a very specific style of training, but also a certain ease and clarity to how they moved," shares Shropshire. "Their skill and engagement inspired me, allowing me to explore particular qualities like speed and elasticity, and to lean into the work’s virtuosity." He selected the eponymous composition, by British composer Judith Weir, "after hearing the score’s first few notes. The opening surprised me, it demanded my attention. And as I listened, the piece continued to challenge my expectations. That excited me. I also liked that the piece was in three parts: a salute, a nocturne, and a lament, each part having a different musical character and suggesting a different choreographic space.

"The work happens in the studio, both practically and conceptually," says Shropshire. "I wanted to explore that tension in the performance and somehow, to also translate that onto film. Because of that, Quinn and I decided to film the work in just one take, in a single shot with no edits—just like in the performance. The dancers ran the piece only once and this is what is captured on film. For me, this gives the film a certain 'liveness' and reflects an experience of being in the studio with the dancers in real time.

"I was inspired most by the experience in the studio—the studio being a very specific, generative space," he continues. "It is where choreographers and dancers work things out; where the impossible is made possible through the alchemy of our attention. The studio is a kind of threshold between before and what comes after, between rehearsal and performance. But it is also a space that questions why we dance and who we dance for.

"I think the final work addresses all these concerns in a simple, abstract way."