Dazzling Ebullience

Spotlight on Bourrée Fantasque

, September 15, 2023

In his Complete Stories of the Great Ballets, Balanchine devotes four pages to his 1949 ballet, Bourrée Fantasque; the vast majority of the text is devoted to a detailed play-by-play of the choreography, almost as though he were notating stage directions. Regarding any historical inspirations, musical choices, or, as was always rare with Balanchine, possible interpretations, he merely writes, “This dance spectacle in three movements has no story, but each of the three parts has its own special character and quality of motion to match the buoyant pieces by Chabrier that make up the ballet’s score.” Premiering just over a year after New York City Ballet’s formation and last performed by the Company nearly three decades ago, Bourrée makes its return to the stage for NYCB’s 75th Anniversary Season with a hint of mystery—and with the promise of a glimpse of the choreographer in his foundational years in the city.

Though composer Emmanuel Chabrier’s name may be relatively unfamiliar to today’s ballet audiences in comparison to the likes of Igor Stravinsky, Peter Ilyitch Tschaikovsky, or Maurice Ravel, his music has been considered an important influence on artists as varied as Claude Debussy, Eric Satie, Richard Strauss, Gustav Mahler, and even Stravinsky. Born in 1841 into a bourgeois family from the Auvergne region in central France, Chabrier’s initial career was in the law; while employed by the Ministry of the Interior for nearly 20 years, he continued studying music on the side and composing his earliest works. Technically an amateur due to his lack of conservatory training, Chabrier would go on to leave behind a number of beloved works in his short career, the most famous of which being his España from 1883. His very lack of formal education in music provided a certain freedom from familiarity or constraint that was much celebrated by his peers and fans, allowing for the development of a singular vocabulary and style.

Perhaps it was Chabrier’s unique voice that appealed to Balanchine, who had been hard at work on crafting a vernacular particular to his own vision and to his new home in America long before establishing NYCB. He had admired the composer’s work for many years, scoring a treasured though long-considered “lost” work with Chabrier excerpts: Cotillon from 1932. Set on the so-called “baby ballerinas” of the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, Balanchine was known to have little interest in reviving this work, though its premiere audience included a figure important to both his career and the history of the Company: Co-Founder Lincoln Kirstein. As The New York Times later noted, Kirstein wrote of Cotillon: “If Balanchine never read Proust, it is of no importance. He absorbed from Chabrier's brilliant music the acrid perfume of adolescence; divinity felt by young dancers at their first ball, heady with their own youth, shyness and insecurity, masking it all in false boredom and the frightened indifference of aching wallflowers at a heartbreak ball.”

While the cast and “characters” of Bourrée Fantasque are decidedly more grown up than those of Cotillon, Chabrier’s orchestral music again inspired a youthful vivacity in Balanchine’s choreography, including visual gags and references to popular dances like the can-can and the tango. Bourrée begins with one of the composer’s best-known works, the Joyeuse marche, a piece, per Balanchine, “so blatantly vivacious that our senses are prepared for the high-spirited geniality,” which proceeds when the curtain rises on the four couples who open Bourrée’s second movement. These dancers are soon joined by four additional women, and, eventually, a lead couple (danced by Tanaquil LeClerq and Jerome Robbins on the premiere), whom Balanchine indicates should include a man who is notably shorter than the woman. This height differential sets up much of the comedy-of-errors that follows, not unlike some of the humorous exchanges in his Western Symphony from 1954. Like the later work, Bourrée’s unique tone emerges from Balanchine’s signature blend of wit and classical rigor, a combination often thought of as distinctively “American” within the history of the art form—or, at the least, indicative of Balanchine’s fondness for Americana. This movement is set to the Chabrier composition for which the ballet is named and continues the circus-like tone of the piece as a whole.

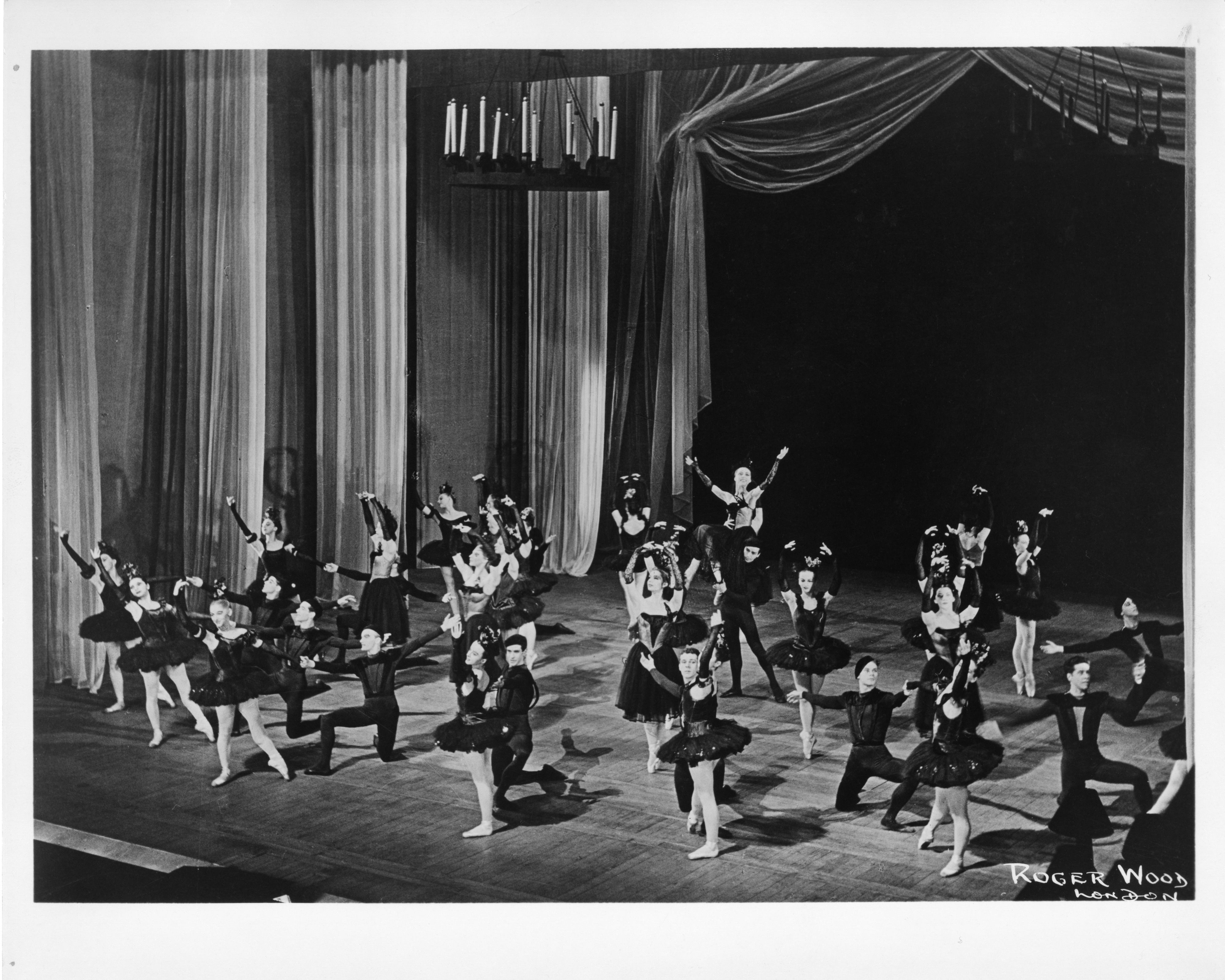

The remaining two movements of Bourrée are set to excerpts from Chabrier’s rather unsuccessful operatic output: the “Prélude” from Gwendoline for the third, which is devoted to a delicate, romantic pas de deux originally performed by Maria Tallchief and Nicholas Magallanes, and the "Féte Polonaise" from the comic opera Le Roi Malgré Lui (The Reluctant King) for the fourth. This last is a joyous, bombastic tune, well-suited to the ballet’s conclusion for the full cast of 42. As Alastair Macaulay wrote in the Times in 2016:

...it moves from comic absurdity, via coolly ceremonious romance, to dazzling ebullience. Even if you think you know how exciting a Balanchine massed-ranks finale can be, the one that ends ‘Bourrée’ proves yet more intense than others, with astounding shifts of geometric formations. There’s one ultra-ebullient sequence where no fewer than four concentric rings of dancers are all moving to, fro, in and out and around, while a ballerina at the center is bursting into the air in lifts like a champagne cork.

Balanchine’s work both on Broadway and for the silver screen in the 1930s and ‘40s can be felt in these June Taylor-esque configurations, whose complexity and drama are infectiously evident from every seat in the house.

The title for the ballet, taken from Chabrier’s piece of the same name, refers to the bourrée, a swift, clog-footed folk dance native to his homeland; it can also be thought of as referencing the term in classical ballet, which describes a small, quick, gliding step. Even in this evolution of a titular term, Balanchine signals the multi-valent quality of this work, which is both lighthearted and rigorous. “Fantasque” translates to “whimsical,” and with Bourrée Fantasque, the choreographer delivers what is essentially a treatise on the whimsical possibilities of a new approach to classical—and neoclassical—ballet, and an appropriately insouciant preface to the creative innovation that would blossom in his American career.

Header and group photo by Roger Wood from the London 1950 tour at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden; photo of Maria Tallchief and Nicholas Magallanes by Frederick Melton from the New York City Center of Music and Drama in 1949.