Studio Visit: Andrew Litton

A Conversation with NYCB's Music Director

, April 28, 2022

“See the music, hear the dance”—It’s one of NYCB Co-Founder George Balanchine’s most oft-quoted adages, and, amongst other interpretations, an indication of the primacy of music to his conception of ballet. The score was often the source of his works’ “narratives,” and he was known to remark that should any particular ballet not capture a viewer’s attention, they ought to just sit back and enjoy the music. The New York City Ballet Orchestra rises to the occasion of these dictums, performing each season, night after night, the varied and often otherwise-unperformed works that accompany the Company’s repertory—pieces as by turns challenging and unique as those composed by Anton von Webern, Sergei Prokofiev, Philip Glass, Charles Ives, and many more.

One composer whose works recur on the NYCB schedule each year is Igor Stravinsky; the collaboration shared by Stravinsky and Balanchine was both uniquely fruitful and singularly impactful on the development of their respective art forms. This year marks the 50th anniversary celebration of the 1972 Stravinsky Festival, an iconic celebration of the composer and his place within the Company’s history. The 2022 Festival will feature a broad sampling of the many works set to Stravinsky’s music, and represents both a vital opportunity for the Orchestra to revisit the composer’s remarkable output, and to step forward with two “solo” performances of un-choreographed pieces.

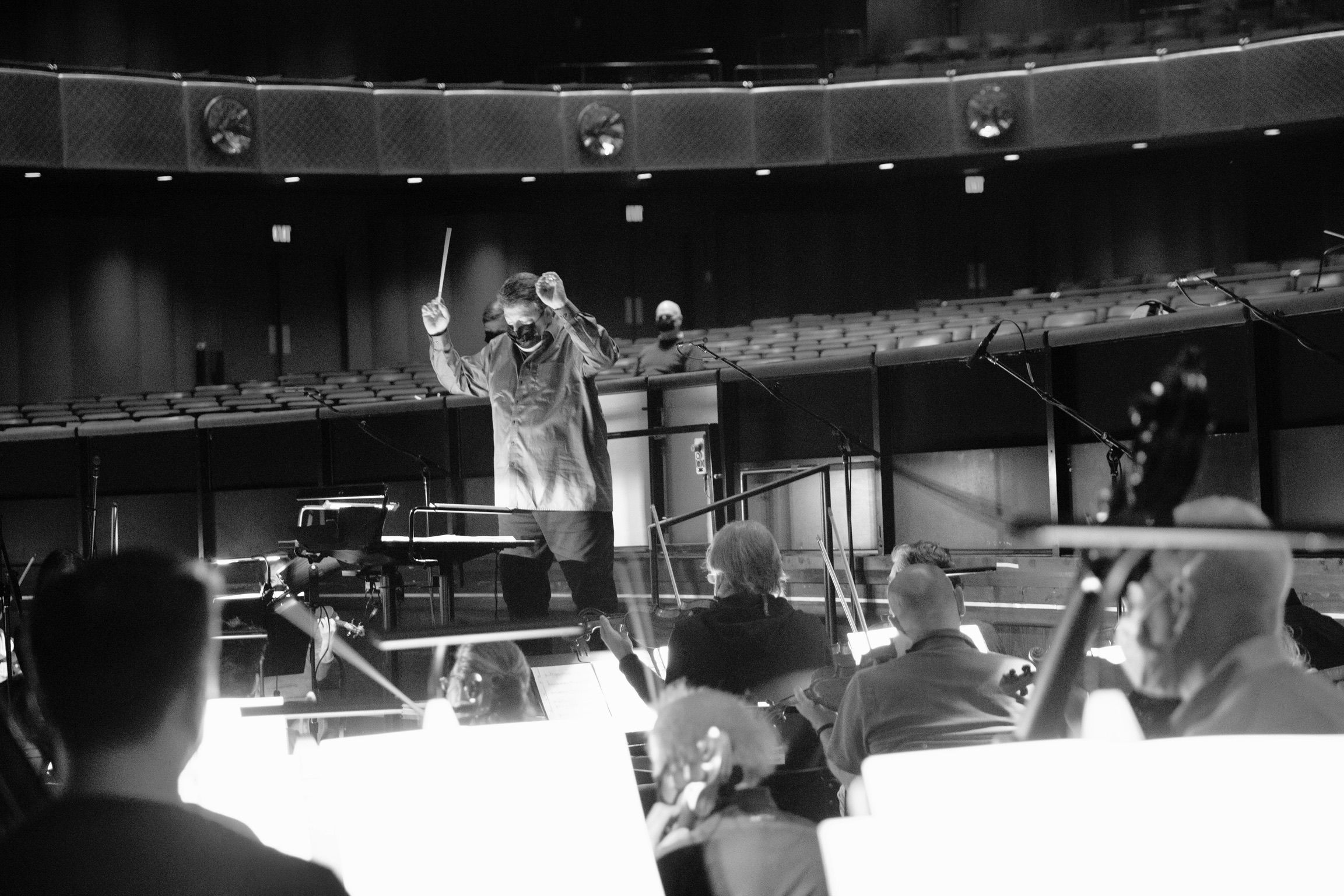

Leading the charge throughout this pivotal Festival for the Orchestra, and all year long, is Music Director Andrew Litton. Since stepping into the role in 2015, Litton has continued to guest conduct leading orchestras and opera companies around the world and add to his discography of more than 130 recordings, all while helming an Orchestra tasked with keeping NYCB’s distinctively-scored repertory musically rich, vivid, and up to the Company’s established standards. We spoke with him shortly before Festival rehearsals were set to begin.

Conversation edited for length and clarity.

Please tell us about your background.

I was born in New York City, on the Upper West Side. I consider myself the real “West Side Story,” because I was born two days after ground was broken for Lincoln Center, and have always lived, or my parents have always lived, in that neighborhood. I went to the Ethical Culture Fieldston Schools, where I got lots of wonderful early chances to musically direct shows, and I began studying piano when I was six.

When I was 10, I decided I wanted to be a conductor, and the the catalyst for that was attending the Young People's Concerts that were then conducted by one Leonard Bernstein; it would make a much better story if I told you it was the very first one I went to when I had this epiphany—it wasn’t, I squirmed like all the other little kids. But the fourth or fifth one I went to, he did a piece called Pines of Rome by Ottorino Respighi. It's an incredibly colorful, visceral piece from the early 20th Century. The way Bernstein described the four vistas in Rome, and then the music played—you could see these vistas! And the end is incredibly loud with extra brass, and [Bernstein] was jumping up and down. I came out of what was then called Philharmonic Hall and said to my mother, “I want to be a conductor.” She just rolled her eyes, because up until that morning, I wanted to be a fireman. Back in the early ‘70s, they had these hook-and-ladder fire trucks and there was a driver required for the back. I wanted to be that guy—so, still up on a platform of some sort. But anyway, I was serious, and from that moment on, piano became a means to an end. I just wanted to conduct.

After that, 30-something years goes by, no involvement with ballet. A week after I graduated from Juilliard with my Master’s, the National Symphony in Washington called and said, “[Former Music Director of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, D.C., Mstislav] Rostropovich would like you to come down and audition for their assistant conductor position.” So I had this amazing double life where I could be assistant conductor, and ask all the inane, stupid questions that you have when you're 22; and in the meantime, go make my London [conducting] debut with the Royal Philharmonic, hopefully showing some level of expertise. It was a fantastic early career and early development, and I was very lucky. A record label took interest in me and I recorded all the Tschaikovsky symphonies, all the Rachmaninoff symphonies, a bunch of American music—all with my first orchestra, Bournemouth [Symphony Orchestra in Poole, United Kingdom]. These were pretty amazing times.

How did you come to work with NYCB?

When the City Ballet was looking for a music director, and my manager at the time said, “Well, what do you think, do you want to try?” I thought, “Sure, it'd be a new adventure, and I could live at home.” So it was Bournemouth, from 1988 to 1994; Dallas Symphony [Orchestra] from 1994 to 2006; Bergen Philharmonic in Norway, from 2003 to 2015; Colorado Symphony from 2012 to 2017; and Singapore Symphony principal guest [conductor] starting in 2017, and continuing now. And then New York City Ballet.

So [my audition] was Coppélia, and, of course, a fantastic score, and it was so much fun. [Former Artistic Director] Peter Martins was very hands-on back then and he had a real appreciation for the musical side of things. He always apologized for his interference, but at the same time, his interference was well-placed. He would demonstrate a tempo to me and conduct the absolutely correct beat pattern while he was singing, so he has definitely got a level of musical knowledge, which was very special for me starting out. I had a large learning curve to master, because I spent almost 37 years conducting sound, and now I'm conducting sight. It's a very different experience.

So, it's been really fun for me, because when it's a concert piece and it's choreography, for example, by Balanchine or Robbins, I try in subtle ways to steer the tempi back to where they should be for a concert hall piece. But when it's a ballet ballet, like Swan Lake or Nutcracker or Sleeping Beauty, then of course the dancers call the tunes, just like the soprano calls the tunes in a bel canto opera. You follow the diva and no questions asked. It's been a fun challenge for me to try and marry these two disparate worlds. Back when Balanchine was alive, and Robert Irving was music director, Balanchine would often defer to Irving; he would say, “Wait, is this the right tempo? No? Okay, fine.” It's the music director's job, I feel, to maintain the integrity of the original work we’re now dancing to as much as possible.

Symphony in Three Movements is another perfect example. It’s a very difficult piece to program as the conductor of an orchestra, because it's an undeniable masterpiece, but it's too short to be on the second half of a concert, and it's too difficult to be on the first half. Obviously, the New York City Ballet Orchestra knows it in its sleep. But for an orchestra that’s never played it before, it's a very challenging piece. So Balanchine, in his own way, made these works survive, and improved them by putting this amazing choreography to them, so that we hear them on an almost annual basis in New York, and in performances that are brilliant. It's so meaningful to me to now be music director of a company that has so many Stravinsky ballets in the repertory.

Tell us about your relationship with Stravinsky’s music.

When I started in 2015, I'd recorded Rite of Spring and Petrushka, I knew Firebird intimately, had toured with it and recorded it as well. That's it. Maybe the odd performance of the Violin Concerto, but the rest of Stravinsky is largely neglected, except for in our Company. Immediately I got to learn Symphony in Three, I got to learn Les Noces, I got to learn, and perform many times, the Violin Concerto, and all the other smaller pieces—and, of course, the triptych that we know and love, the Greek Trilogy. I'd never conducted Agon before, or Orpheus, though I'd done Apollo. To have this chance to conduct all three in one evening, with this incredible choreography! Orpheus may be the least successful of the three pieces from a musical point of view, but Balanchine made such a success of it that it's actually the symbol of the Company—Orpheus’ lyre. It's incredible to be part of that world, thanks to Balanchine and Stravinsky. The two of them fed off of each other in a most fascinating and stimulating way, and we’re the beneficiaries. It's so exciting to carry that on.

When I did my See the Music program on Orpheus, I read a Balanchine quote, which I can share with you now:

He would ask me, for example, ‘How much music do you want for the variation of Orpheus?’ If I asked for one minute, 20 seconds or one minute, 15 seconds, he would reply, ‘Well, let's make it one minute, 16 seconds.’ And that's how he would write the music. When I receive the score from Stravinsky it is completely different than what I asked for. But because I know him, I know what to expect. It's easy to adapt my choreography to his music because it is like a corset that holds you firmly. It's good to have somebody who can do that.

Those are such sweet words. And unbelievably meaningful. To have that kind of relationship with the composer, that kind of understanding—that must have been so special. We bear the fruits of that with our Greek triptych, but also all the works that Balanchine did for the first Stravinsky Festival, which are amazing.

From my point of view, it's just so fantastic. If I have to show somebody, “This is the Company I work for,” it would either be Serenade or Symphony in Three. I think of all the Balanchine ballets, these to me are so perfect with the music—elevating the music, which is what you want, in an ideal world, in ballet—making the music even better. Maybe I'm being unfair by singling pieces out. But Symphony in Three, when I was a kid going to City Ballet as a Juilliard student, I was like, “This is so amazing, how somebody came up with these moves to this music.” Little did I know, I would be involved someday.

What are some of the unique moments and challenges from the Greek Trilogy that stand out in the rehearsal process or performances?

Well, the interesting thing is Apollo—which I've done the most, because we do it often on its own—is really all about the dancers. It's very much a dancer-oriented ballet, which seems weird to say. Whereas Orpheus has a lot more theater, in a way; you don't have to worry so much about the tempo because there's more dramatic action. Agon, once you hit the groove, there is one tempo for this piece, there's no negotiation. Agon is one of those works because of its compactness, as well as its modernity. It's perhaps the piece that's least open to interpretation, from a musical standpoint—you just have to make sure all the i's are dotted and the t's are crossed and that it's as clean as possible. Orpheus has the most scope for interpretation, because there’s much of it that's not particularly danced to. Apollo is a ballet ballet, as I always like to distinguish—it's very much dancer-dependent. And an incredible piece, by the way. It's my favorite of the three, just selfishly speaking. There's no explanation I can give to justify that. I just love conducting Apollo. I think it's so beautiful.

The chance to conduct and perform all three in one evening provides a fantastic exposure to three periods of Stravinsky's writing. It's amazing because you could say, “A whole night of Stravinsky, won’t it all sound the same?” Of course, these pieces couldn't sound more different if you tried. I think it's fascinating to have the opportunity, thanks to Balanchine, to perform these three pieces, in context, in one evening. We’re talking nearly 30 years of musical composition in just this trilogy.

Balanchine had a way of making these concert pieces have a shelf life, as I said at the beginning of this conversation, far beyond normal. Rubies. The Violin Concerto. We play it so often—if you look at orchestra programs, you may be lucky to find one orchestra playing it this year, somewhere. It's just not done, even though it's a great piece and violinists love the challenge of it. So we're very lucky to have this treasure trove of great Stravinsky music. There are so many other works, I'm not even touching the surface. We have 23 ballets in the active repertory, and at some point the Company has done something like 70 pieces set to Stravinsky—basically everything the man ever wrote.

The extraordinary thing to me is that Balanchine was absolutely against choreographing Rite of Spring, to the point that he hated people who did. He didn't understand that. His reason was, it was perfect. It didn't need to be danced to. But he's overlooking one thing: It was meant to be danced to. That's what Stravinsky wrote—he was under the employment of Serge Diaghilev. On the other side of the coin, Balanchine was absolutely brilliant in knowing what a masterpiece the work was. From a historical point of view, it is one of the most impactful works anybody ever wrote, anywhere, any time; Rite of Spring changed the course of musical history, and Stravinsky was relatively young when he wrote it. To think that, here's this genius who, first of all, writes Firebird, which is gorgeous and beautiful, and everybody loves; Petrushka, which we also don't do as a Company; and then Rite of Spring—in 1909, 1911, and 1913. If Stravinsky had died after he wrote Rite of Spring, he still would have made the biggest impact you can imagine. But the fact that he lived for so much longer and was able to collaborate with Balanchine is to our strength. We're so lucky to have these incredible works.

What are you particularly excited about within the Stravinsky Festival?

The short answer is, I'm just looking forward to being there virtually every night and conducting this great music. The long answer is, every piece by Stravinsky has its challenges musically—and, of course, choreographically, which I have to be abreast of; I have to know what those challenges are so I can make everybody comfortable. It's exactly this kind of artistic challenge that, as music director of New York City Ballet, I find so inspiring and so stimulating, because this is not a normal day at any other office. It's very much unique to our Company and our world. I'm looking forward to every piece because they each come—even Circus Polka comes with its own challenges. And I'm also thrilled that there'll be two occasions when the Orchestra gets to show themselves as the amazing ensemble they are. That was tricky, because Stravinsky’s short pieces tend to be incredibly gritty and dissonant. These two pieces I chose [Fireworks and Suite No. 2 for Small Orchestra] are sort of traditional and easy to enjoy from a listening point of view—without Balanchine's choreography to distract us, or anybody’s choreography to distract us, the music has to stand up on its own. I feel that the two pieces I chose do that.

Please describe the role of the music director as you see it. What might audiences not realize about this essential role?

I think the biggest thing is, there are a lot of ballets that we do in New York City Ballet that are older, that have a tradition, and that have a performance legacy. What I try and do as music director is come in with my years of experience as an orchestral conductor, and apply that to the legacy of the Company, and try and find a way, as I said earlier, to integrate what I believe the composer's desire for tempo was, and what the dancers need to actually execute the incredibly challenging steps that the choreography demands. It's very important that the musical integrity be maintained at all times, and that the Orchestra is constantly challenged to play at the highest possible level every night. The other aspect is to make sure that new choreographers coming in realize they have a 64-piece orchestra at their disposal, that this is very much what New York City Ballet is. We try very hard to butt-in when it looks like a composer is erring towards going for a tape, unless it's clearly electronic.

The Orchestra is constantly evolving and changing, and it's my job to be part of the auditions, and, with the orchestra committee, pick the best players possible, because that just improves the standard of the orchestra. It's like a “rite of spring,” a rebirth process. Every new player that comes in brings something new to the institution, just like new dancers. Basically, I mind the store musically, along with Associate Music Director Andrews Sill and Resident Conductor Clotilde Otranto, just like the repertory directors mind the store choreographically. I think that's the easiest way to put it.