39 Nutcrackers in One Season: Edward Gorey & George Balanchine

An Interview with Mark Dery, Edward Gorey’s Biographer

, December 17, 2018

I have now reached the point where I can see Patty McBride doing every ballet, even those she hasn't danced.

— Edward Gorey

In his lifetime, the prolific Gorey wrote and illustrated over 100 books, including classics such as The Gashlycrumb Times, The Doubtful Guest, and The Gilded Bat (in which a little girl obsessed with dead birds transforms into a goth-chic ballerina), and did extensive illustration work in publishing and beyond, like the opening credits to PBS’ Mystery series, which delighted and frightened a generation of kids watching public television with their parents.

Gorey was a paradoxical figure; hardly the dour British Victorian that one could easily imagine by his work, he was a brilliant American eccentric who devoted himself to words and the art of the perfectly drawn line. Most notably, one of Gorey’s great loves was New York City Ballet, and more specifically, George Balanchine. He was an ardent fan of Balanchine’s genius as a choreographer, and was a known presence in the crowd at Lincoln Center in his full-length fur coat. He religiously attended the Company’s repertory seasons for over thirty years, would often hold court on the Promenade, critiquing the evening’s ballets. But he had a special affection for The Nutcracker, a ballet where his attendance was a ritual: in fact, over two seasons, he attended 78 consecutive performances — 39 in one season alone.

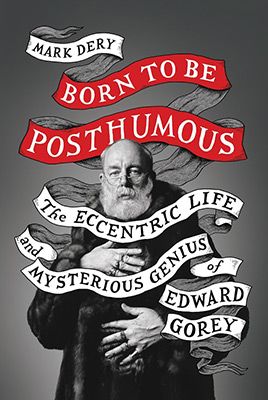

To learn more about Gorey’s passion for the work of George Balanchine, his vision of The Nutcracker, and NYCB, we talked to cultural critic Mark Dery, whose recent and definitive biography of the artist, Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey, is available now.

What was a surprising revelation that emerged from your research into Edward Gorey’s passion for George Balanchine’s work in ballet?

Mark Dery: What emerged over time, and gradually came into sharp focus, was not only how modern Balanchine was in his own way – which is hardly a revelatory thunderbolt to students of ballet and admirers of NYCB. What I discovered was that Balanchine’s neoclassicism was radically modern. He blew off all the [Sergei] Diaghilev bric-a-brac of 19th century theater, reimagined the dancer’s body, streamlined ballet and abstracted it to a degree, and premiered new pieces by [Igor] Stravinsky. In pieces like Agon, the dancers begin with their backs to the crowd, and they’re wearing warmup outfits. This stuff is unimaginably radical when it’s happening.

I do believe that Gorey, in his radical narrative compression – which owes something to his love of Taoism, Asian spirituality, Zen Buddhist poems, the limericks of Edward Lear, and surrealist proverbs and one-liners – there’s also the legible influence of Balanchine. Take Gorey’s haiku-like narrative compression and the fact that there’s never an excess line, every stroke of the pen must be there or the whole thing comes down like a house of cards. In its own way, it’s very “Balanchinian.” I think that makes both of these artists modernists.

Did you find a relationship between Gorey and Balanchine’s art?

In one of the chapters on Gorey’s adoration of Balanchine and New York City Ballet, I tease out all these lines of connection between them. Balanchine is, in a sense, using the dancer’s body to draw in the air. Inversely, Gorey is creating almost little theater pieces within the covers of a book. Everything is seen as if it’s parenthesized by the proscenium arch, and his characters are always viewed as if they’re onstage.

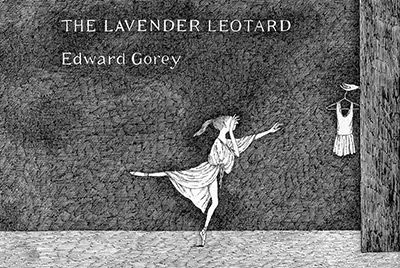

What was your take on Gorey’s book The Lavender Leotard: or, Going a Lot to the New York City Ballet (1973)?

It first appeared in Arlene Croce’s ballet magazine, and it’s really more of a series of single-panel gags, so to speak. There’s a theme that’s ribboned throughout it, but unlike many of Gorey’s books, it’s sort of a series of cartoons that are concatenated, joined together by a running joke, which is the penurious nature of early NYCB. It’s not just for balletomanes, but very specifically for acolytes of the NYCB cult who remember the Company’s City Center days.

So all of the jokes, every one of those one-liners in The Lavender Leotard, is very much an inner-circle joke about how they had to scrimp and save and pinch here and there and piece together costumes and backdrops from cast-off oddments from other ballets.

It’s intriguing—because horrible pun very much intended—The Nutcracker is one of the moldiest chestnuts in the ballet repertoire from the perspective of a casual ballet-goer and also from the perspective of many world-weary, battle-scarred balletomanes who pride themselves on a far more rarified and urbane take on Balanchine. It’s de rigeur to pooh-pooh The Nutcracker as Balanchine’s concession to mass taste.

Gorey ended up loving The Nutcracker, and his friends thought it was incalculably perverse that he attended every performance of every Nutcracker in a given season. There is a fabulous quote from him in the interview collection Ascending Peculiarity, where he talks about how The Nutcracker’s Act 1 family party is kind of a platonic ideal of a family gathering, and how family gatherings never really are that way.

There’s a real melancholy to that quote – that it’s this exquisitely beautiful, impossibly charming moment where everyone is rapturous, and everyone’s getting along wonderfully. Gorey says that after this party is all over, it will burst like a soap bubble and be lost to all time. He burst into tears once when he was watching the ballet, and I think it really does gesture to something repressed in his own background. I see his comments as very much suffused with the melancholy of someone who, in some very real sense, didn’t experience childhood the way most “normal” people do, and so he lived vicariously through that scene in The Nutcracker and imagines a very romanticized, idealized childhood moment. Gorey never had a childhood. Due to his precociousness and off-the-charts IQ, he was like a little adult in velvet breeches.

What did Gorey appreciate about Balanchine’s work?

He had a real artistic genius’ ability to zero in on genius in other artists, and he appreciated Balanchine at that level. As he famously said in one interview, “What makes Balanchine so extraordinary is that when you see his dances, you feel ever after as if the steps were absolutely perfect for the music, and there can be no other choreography.” It was literally as if the music was becoming flesh before his very eyes. And it was that absolute clarity and concision and complete mastery of the medium that I think struck such a responsive chord with him. In the same way that Balanchine famously said, “Ballet is woman,” I daresay Gorey would say ballet is Balanchine.

Did they ever meet?

They would periodically orbit past each other at cocktail parties, because of course Gorey knew some of the dancers passingly. Gorey always claimed that the background cacophony of cocktail parties was infelicitous to conversation for him, because he was slightly hard of hearing, and that would also make it difficult for him to understand Mr. B., especially through his Russian accent.

But I think it had equally to do with Gorey being a bit tongue-tied around him. And as he put it in one interview, “I mean, what would you say to God?”

Mark Dery’s biography of Edward Gorey, Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey is now available from Little, Brown. Dery is a cultural critic whose writings on media, technology, pop culture, and American society have appeared in Artforum, Cabinet, Elle, The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, Rolling Stone, Salon, Spin, and Wired, among others. He is the author of numerous books, and lectures frequently in the States and abroad.

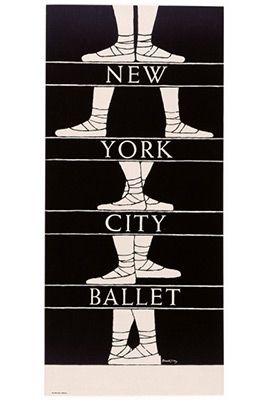

Book images courtesy of Little, Brown. Archival Nutcracker photo © Martha Swope. NYCB Poster Design by Edward Gorey, 1974-5.