Dancing Emanon

A Gift from Choreographer Jamar Roberts

, February 14, 2022

“See the music, hear the dance”—it’s one of the most iconic quotes from NYCB Co-Founder George Balanchine. The phrase captures his love of and devotion to the often challenging, complex music he chose to work with, as well as his penchant for abstract, non-narrative ballets; but it’s most often repeated in reference to the primacy of musicality in his choreography. This same aphorism arose several times when we spoke with the NYCB dancers who originated roles in choreographer Jamar Roberts’ Emanon — In Two Movements, which premiered on our Lincoln Center stage on February 3.

“I can see Balanchine’s influence so clearly in this work,” says Soloist Emily Kikta. “At every point in the process, Jamar emphasized how the dance needed to match or highlight the music. Right up until the premiere he was making sure we were dancing with the right musicality at all times so that we showed the music with our bodies.”

Corps de Ballet Member Jonathan Fahoury similarly noted the presence of Mr. B in Roberts’ choreography for Emanon. “You see the inspiration of Balanchine coming through the work from the musicality, the pace of the ballet, and the intricacies of the steps,” he says. “This ballet is no easy task. There is the feeling of giving everything you have at that moment in time. Which is the very thing that Balanchine’s ballets bring out of dancers.”

Roberts’ choice for the work’s score shows a Balanchine-esque admiration for contemporary composition as well—particularly because the music isn’t immediately recognizable as suited for ballet. Released in 2018 as a three-disc or three-vinyl set with an accompanying sci-fi graphic novel, Wayne Shorter’s Emanon combines freewheeling bebop-inflected jazz with an upbeat orchestral counterpoint, and a multiverse-spanning philosopher’s tale. The music juxtaposes improvisation and pop culture with the classical, a fitting metaphor for the meeting of modern and neoclassical dance realized in Roberts’ choreography.

“Heading into a new work, you never really know what to expect,” says Soloist Emma Von Enck. “It was exciting yet intimidating to hear the music that first day. Often jazz can be less strictly structured in its form than

“We spent so much time understanding the music and its accents and swerves,” adds Soloist Jovani Furlan. “I’m still working on it; even in the premiere I found new nuances that I hadn't explored in the rehearsals yet.”

As each of the dancers related, Roberts tempered the wild, unfamiliar qualities of the score with a clear yet malleable vision of the work. “Jamar came in knowing what he wanted from the get-go,” says Furlan. “The first thing he did was the solo I performed, which was originally choreographed for [Soloist] Harrison Ball. In the minute and a half solo, there are no wasted moments, each step connects to the next in the most coordinated and musical way.”

“I feel like Jamar saw us as specific dancers, and made all these little dances [within the work] that are suited specifically to our strengths,” adds Principal Dancer Anthony Huxley. “He was open to making sure we felt comfortable in the dance so that it really showed off each individual dancer.”

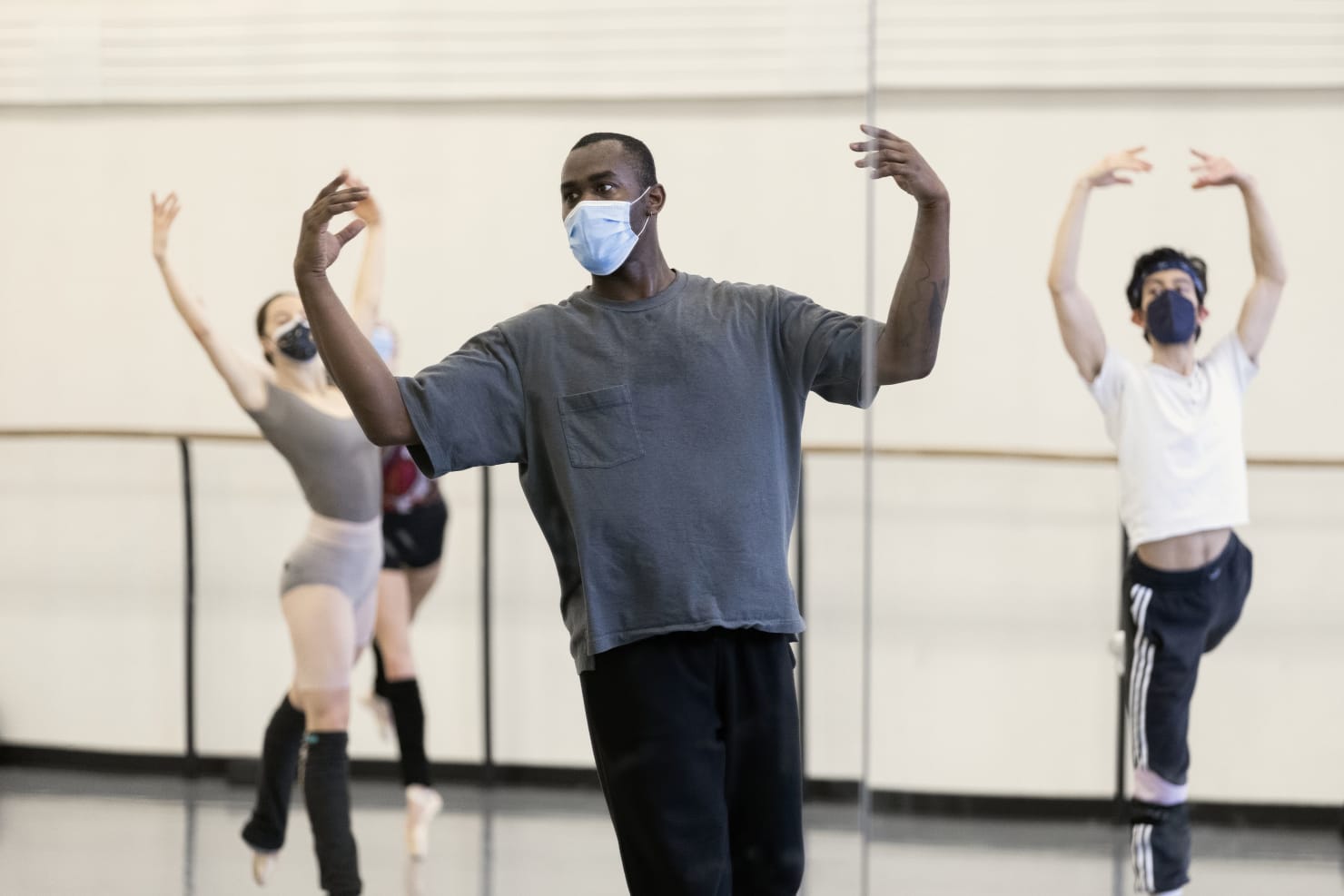

Rehearsing Emanon

“Working with Jamar has been a dream and a pleasure, because he is such a kind, warm person, and he feels very open and receptive in the space, so it's more of a conversation between the two of us when he comes into the room,” agrees Principal Dancer Indiana Woodward. “He would set the steps and the image that he wanted, and the work that he wanted to see on each individual—and he seemed like he had done his research and catered to each dancer—but then once it was on the dancer, he molded it and shaped it so that it really fit us as well as his vision. He was giving us an opportunity to understand the work, and then make it our own, which was pretty special. And then at the end of the process, he was like, ‘I've given you what I want to give you… This is yours now.’ I thought that was really special for a choreographer to tell us, and it made us feel like it was a piece that was close to our hearts as well as his.”

This intermingling of Roberts’ vision with the unique attributes and strengths of the dancers reflects a coinciding blend of classical technique with the choreographer’s vocabulary. While that mixture is evident throughout the work, one solo in particular, created on Fahoury, stands out as a singular utterance. “This solo means a lot to me—I don’t even know where to begin,” says Fahoury. “I didn’t know what to expect going into our first rehearsal, but as soon as he started creating the material with me, I was thrilled. It felt as though he was taking steps that felt authentic within him and letting them translate organically within me.

A sense of freedom within an established structure, a collaboration that merges both defined classical footwork and a spirit of spontaneity: Emanon reflects the score not only in the details, but in the way in which it was created. “Jamar expressed a clear vision while simultaneously giving the dancers room to experiment,” says Von Enck. “Just before the premiere, he explained that his role as choreographer was finished and that he now gave the ballet to us. As classically trained ballet dancers, we spend most of our days trying to mold ourselves to specific roles. I found Jamar’s approach to be inspiring and liberating. We spent weeks building the framework of the piece and then were given license to experience freedom within that structure. During rehearsals, if I messed up, I would frantically utter an apology, telling him I would get it next time. He assured me that I already had the part, and he was not concerned. He knew I would get it.

“Some days can feel like a never-ending audition as we try to live up to others' expectations, as well as our own,” adds Von Enck. “Throughout this process, we were encouraged to be our genuine selves in the studio, whether it was a good day or not.”

The environment developed within the rehearsal studio is perhaps more essential now than in previous years, as the dancers and the artists they work with return to a shared space after so many months of uncertainty and isolation. “I got to work with both Sidra Bell and now Jamar on new works for NYCB since the pandemic [began],” says Kikta. “It feels different now, perhaps more intimate. There’s a sensitivity to how chaotic and confusing so much of what is going on right now is, and I feel that we are all just meeting each other where we are each day and seeing what comes of that. Also, after spending so much time trying to create via Zoom or from long distances, sharing the same physical space makes creating dance seem easier and more organic. After many months of feeling so much resistance in trying to create dance, it’s nice for it to feel easy, and even natural, again.”

“It kind of felt like riding a bike,” agrees Huxley. “At first I thought it would be really strange, not having rehearsed anything and getting to find my way again. But after a couple of days, it just felt normal again, and it felt good to feel like nothing has been lost. The time might’ve been lost, but we just got right back to it.”